Akira Isogai

University Professor, the University of Tokyo

He received Ph.D. from the University of Tokyo in 1985. He was appointed as a Research Associate at the University of Tokyo in 1986 after working as a postdoctoral fellow in the U.S.A. He was promoted to Associate Professor at the University of Tokyo in 1994 and a Professor in 2003. He has been in his present position since 2020. His research fields are cellulose chemistry and bio-nanomaterials science. He received Marcus Wallenberg Prize in 2015, Honda Prize in 2015, Fujihara Award in 2017, Japan Academy Prize in 2019, Esaki-Reona Prize in 2023, etc.

The effective utilization of plant cellulose and its expansion in quantity are highly expected for creation of a sustainable society. This is because cellulose is a renewable material that fixes CO2 in the atmosphere. In various cellulose materials, cellulose nanofibers (CNFs) prepared from plant cellulose fibers are attracting attention as new bio-based nanomaterials. It has already been known that plant cellulose fibers are aggregates of crystalline nanofibers called “cellulose microfibrils (CeMFs).” However, because CeMFs are strongly bound to each other by numerous hydrogen bonds in each cellulose fiber, individual CNFs separated from CeMF bundles have been impossible to prepare and use as nanomaterials. We have reported that fully nano-dispersed CNFs can be prepared by catalytic oxidation of plant cellulose fibers under aqueous conditions at room temperature and normal pressure. In this paper, the method of preparing CNFs is described, and their structures and functions are reviewed with related research achievements.

It is necessary to sever all inter-fibrillar hydrogen bonds in cellulose fibers and to apply efficient repulsive forces to once-separated CeMFs to prevent their re-aggregation after preparation of CNFs stably dispersed in water or another medium.

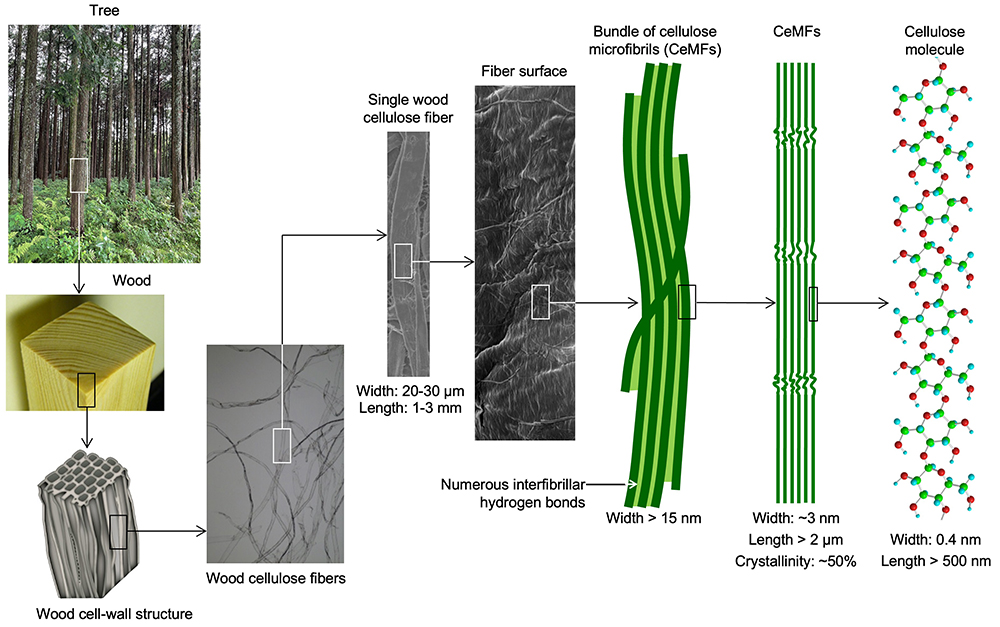

Plant cellulose forms hierarchical structures, and CeMFs are crystalline natural nanofibers forming the smallest elements next to cellulose molecules in cellulose fibers. The CeMFs have a uniform width of ~3 nm, and form crystalline nano-structures consisting of 20-40 fully extended, almost orderly packed, cellulose chains. Therefore, each plant cellulose fiber is an agregate of numerous CeMFs, which adhere to each other by forming strong interfibrillar linkages created by numerous hydrogen bonds. Furthermore, no bent cellulose molecules are present in each CeMF, which has a distinctive structure that is different from its counterparts in synthetic polymer fibers and regenerated cellulose fibers, such as rayon, produced by dissolving and regenerating cellulose, or other natural polysaccharides like starch (Fig. 1).

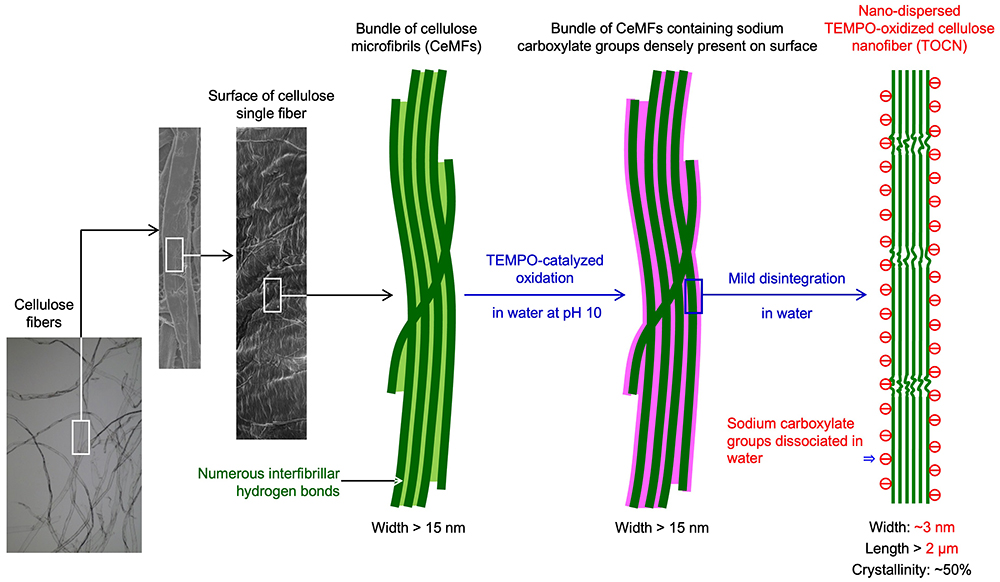

Water-dispersions of microfibrillated cellulose (MFC) are obtained from plant cellulose fibers suspended in water by applying mechanical shear forces using a high-pressure homogenizer or grinder. MFC contains some nanofibrillated structures owing to CeMFs. However, complete nanofibrillation of cellulose fibers to form individual CNFs with ~3 nm widths cannot be achieved only by mechanical treatment. It is necessary to apply some position-selective chemical modifications on the crystalline CeMF surfaces in cellulose fibers as pretreatment for achieving complete nanofibrillation by mechanical disintegration in water. Here, electrostatic repulsive or steric repulsive forces should work between all the CeMFs, while maintaining the original crystalline structures of CeMFs and morphologies of cellulose fibers.

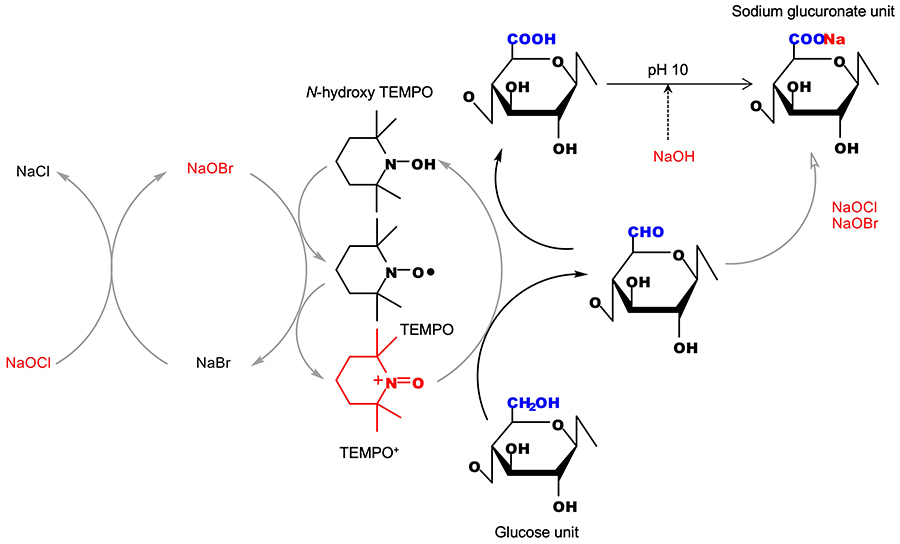

We have investigated the TEMPO-catalyzed oxidation of polysaccharides such as cellulose and chitin under aqueous conditions at room temperature and normal pressure1-5. TEMPO is an acronym for the 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl radical, which is a water-soluble and stable nitroxyl radical. TEMPO-catalyzed oxidation is similar to enzymatic reactions in living bodies, and selectively oxidizes the primary hydroxy groups (C6-OH) of polysaccharides to sodium C6-carboxylate groups (Fig. 2)1-4. When this TEMPO-catalyzed oxidation is applied to plant cellulose fibers with cellulose I crystal structures, the original fibrours morphologies, crystal structures, and crystallinities are unchanged while the carboxy group content increases from 0–0.06 to > 1 mmol/g1-7.

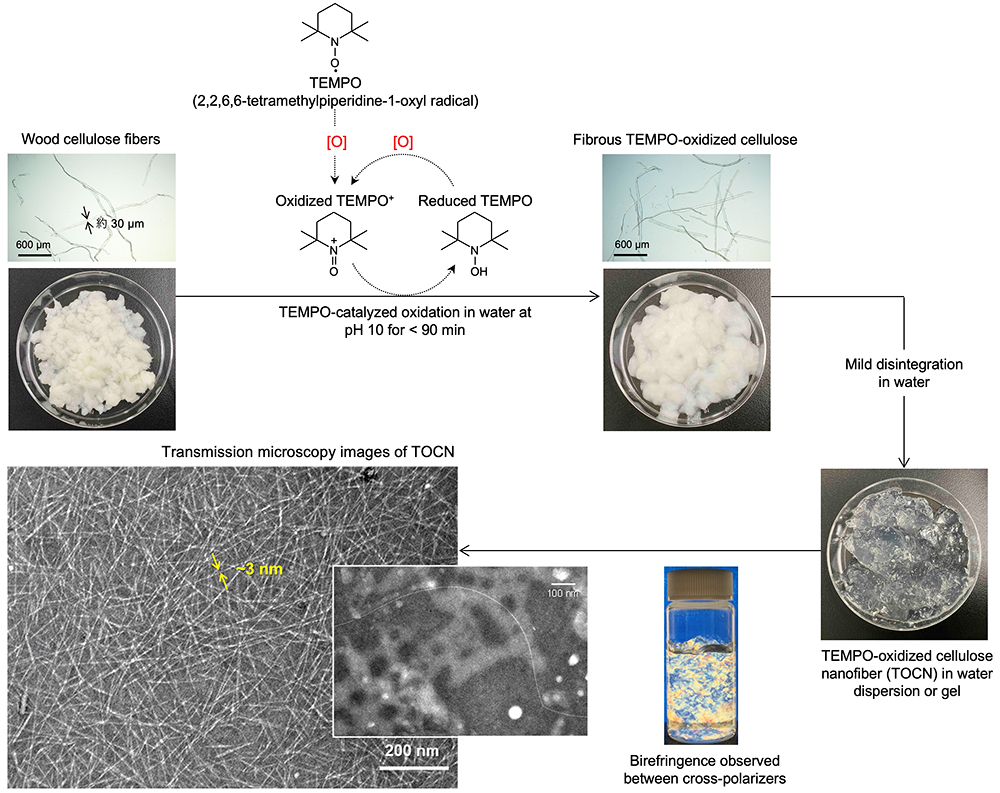

When plant cellulose fibers are oxidized by the TEMPO-catalyst system under appropriate conditions, their carboxy content increases to > 1 mmol/g, while maintaining the original fibrous morphologies. These carboxy group-rich plant cellulose fibers are suspended in water, and then the suspension is subjected to gentle mechanical disintegration using an ultrasonic homogenizer or high-pressure homogenizer. The fiber suspension is then turned to a highly viscous and transparent gel. When these gels are sufficiently diluted to < 0.01% and observed by transmission electron microscopy or atomic force microscopy, we observed completely individualized TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers (TOCNs) with a uniform width of ~3 nm and average lengths of > 500 nm (i.e., their average aspect ratios, length/width, are > 160) (Fig. 3)1-6.

As shown in Fig. 4, the primary hydroxy groups (C6-OH) exposed on the crystalline CeMF surfaces in each plant cellulose fiber are almost entirely and position-selectively oxidized to sodium of C6-carboxylate groups. The high density of these anionic groups enable effective repulsive forces working between CeMFs during subsequent disintegration process in water5,6. As a result, plant cellulose fibers with widths of ~30 μm are fibrillated or downsized to ~3 nm, which is 1/10,000th the width of the original fibers, yielding TOCN-in-water dispersions (Fig. 3).

The unique and characteristic nano-structures and functions of TOCNs could be effectively utilized in applications. TOCN-in-water dispersions form gel-like structures with high viscosities and high elastic moduli when no shear force is applied because the gels consist of entangled structures of TOCNs with large aspect ratios. When high shear forces are applied to the gels, the entangled TOCNs are released, allowing them to align in the shear direction, thereby lowering viscosity. Because of these large gaps, even when the TOCN content of the gel is low, TOCN-in-water dispersions exhibit high shear-thinning characteristics. Dispersions with these properties are utilized as ink dispersants for ballpoint pens and metal particle dispersants for water-based metallic coatings of automobiles.

Each TOCN has a high density of anionically-charged groups on its surface, and TOCN-COONa (Na: sodium ion) can be converted to TOCN-COOM (M: various other metal ions) by counterion exchange in water. Furthermore, the sodium C6-carboxylate groups densely present on the TOCN surfaces may be used as sites for ionic binding of various cationic polymers, nanoparticles, and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), enabling the development of new functional materials from TOCNs.

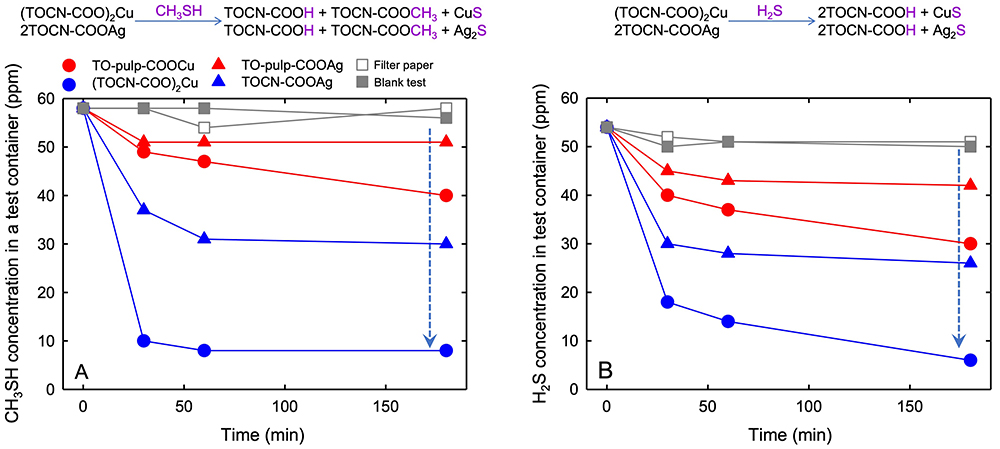

For instance, by introducing copper or silver ions as counterions into TOCNs, TOCNs function as super deodorizers against methyl mercaptan, hydrogen sulfide, or ammonia gas. Because TOCN-COOM has a larger surface area than fibrous TEMPO-oxidized cellulose-COOM, TOCN-COOM efficiently adsorbs the above gas to form odorless compounds (Fig. 5)8,9. When silver or gold ions are introduced onto TOCN surfaces by counterion exchange, and silver or gold nanoparticles are formed in situ on TOCN surfaces by reduction, the resulting area of the TOCN-metal nanoparticle surface is enlarged increasing the efficiency of catalytic functions10-13. The selective gas permeability and barrier properties of TOCN/MOF composites may be attributed to assembly of MOF nanoparticles on TOCN surfaces14.

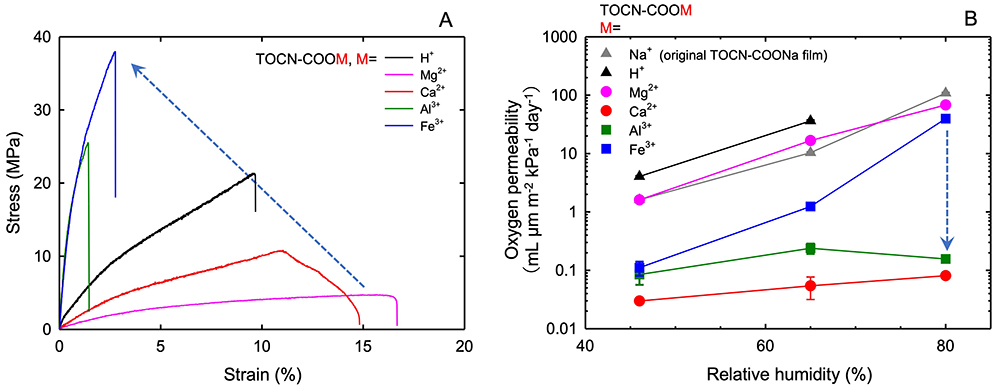

Transparent and uniform TOCN-COONa films are prepared from TOCN-COONa-in-water dispersions by casting and drying. Because of electrostatic repulsions between TOCN in the TOCN-COONa film, the anionically surface-charged TOCN elements form close-packed aggregates with crystalline structure, resulting in films with low porosity and high density. Therefore, the TOCN-COONa films exhibit extremely high oxygen barrier properties under dry conditions15-17. However, because TOCN-COONa is highly hydrophilic, the oxygen barrier properties of the films are lost under high humidity conditions. When TOCN-COOH and TOCN-COOM films are prepared by immersing the TOCN-COONa films in a dilute acid and metal chloride solutions, respectively, these films have high wet tensile strength and high oxygen-barrier properties under high humidity conditions, depending on the metal ions introduced (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 6A, the TOCN-COOM films with iron and aluminum counterions exhibit high wet tensile strengths. The TOCN-COOM films with calcium and aluminum counterions show high oxygen barrier properties even at 80% relative humidity (Fig. 6B)18.

When the fibrous TEMPO-oxidized cellulose-COOH is suspended in water, and an amount of quaternary alkyl ammonium hydroxide (e.g., [CH3]4N+OH-) equimolar to the amount of carboxy groups is added to the suspension, fibrous TEMPO-oxidized cellulose-COO-+N(CH3)4 is formed without affecting the original fibrous morphology of TEMPO-oxidized cellulose-COOH. These fibers containing alkylammonium C6-carboxylate groups can be converted to TOCN-COO-+N(CH3)4 dispersions by mechanical disintegration in water or organic solvents, achieving surface-hydrophobized TOCNs19-24.

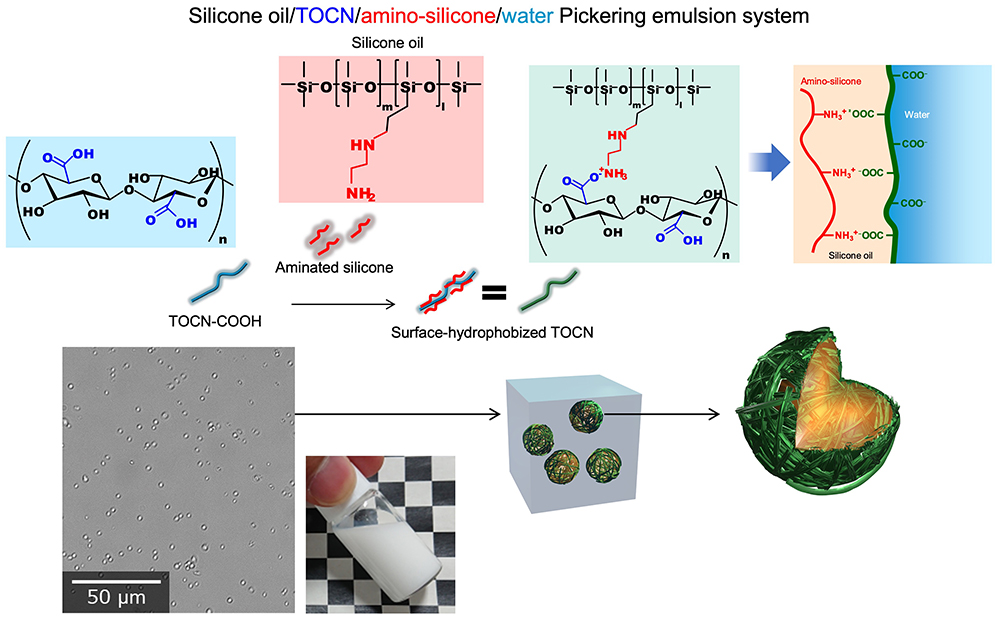

Water-based Pickering emulsions composed of silicone oil/TOCN/aminosilicone can be prepared using salt formation between protonated carboxy groups in TOCN-COOH and amine groups in aminosilicone. The hydrophilic carboxy groups in TOCNs are hydrophobized with aminosilicone molecules by ionic linkages, and these TOCN/aminosilicone complexes can efficiently form Pickering emulsions of silicone oil stable in water. These emulsions exhibit excellent performances as release agents and coating materials over the fluorine-containing materials (Fig. 7)25.

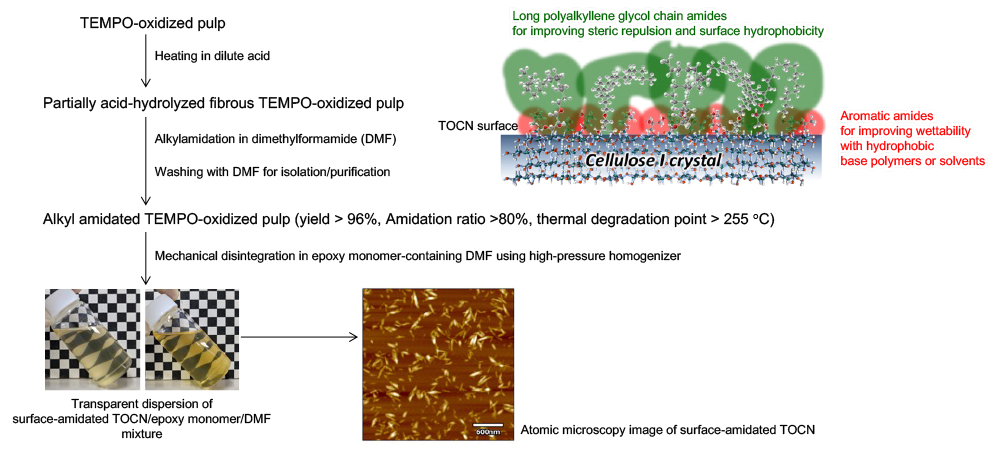

One expected application of CNFs in large quantities is as a lightweight, high-strength composite material for mobility devices, prepared by compounding CNFs with hydrophobic resins, plastics, and rubbers. The use of CNFs has been reported to improve the recyclability of composites, compared to glass fiber-reinforced polymer composites. However, TOCNs are extremely hydrophilic, and the solid contents of TOCN-in-water dispersions with high aspect ratios are lower than 5%. This makes the preparation, storage, transportation, and handling of TOCNs difficult and costly. Furthermore, during thermal molding or the compounding process using conventional equipment with hydrophobic polymers, even when initially nano-dispersed TOCN-in-water dispersions are used, TOCNs are prone to forming aggregates in polymer matrixes. TOCN aggregates in polymer matrixes result in high modulus but low toughness. Additionally, TOCNs often undergo thermal decomposition and discoloration during thermal compounding process, preventing the effective development of the nano-structures and characteristics of TOCN composites.

Under these circumstances, efficient alkylamidation processes of carboxy groups on TOCN surfaces have been developed to improve thermal resistance and nano-dispersibility of TOCNs in hydrophobic resins, resulting in highly transparent, strong, and tough composites with high thermal dimensional stability even when the TOCNs content is a few percent (Fig. 8)26,27.

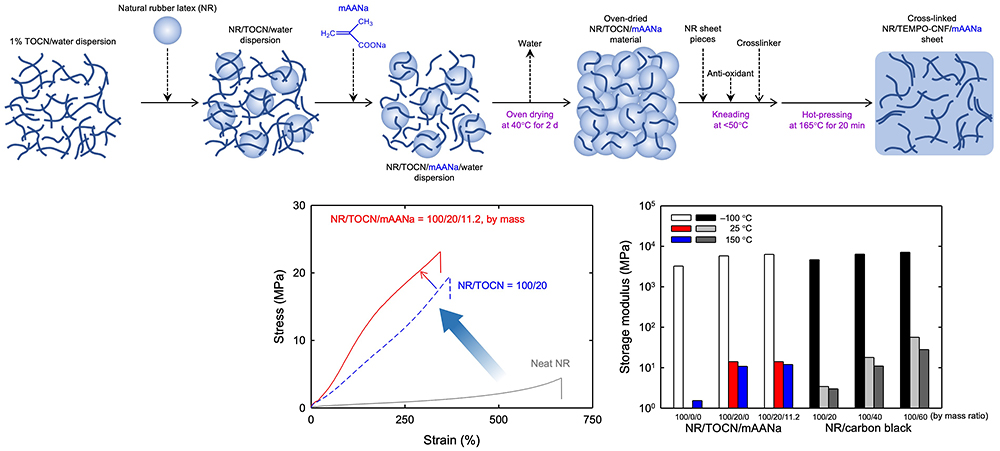

Furthermore, an efficient oven-drying method was developed from mixtures of aqueous natural rubber latexes and aqueous TOCN dispersions for preparing rubber/TOCN master batches. The natural rubber/TOCN composites prepared from the master batches by dilution with natural rubber sheet pieces and applying high-shear forces exhibit high mechanical strength, modulus, toughness, water resistance, and abrasion resistance, making them environmentally suitable for partial replacement of conventional petroleum-derived carbon black28-34. The natural rubber/TOCN composites containing 20 parts TOCNs exhibit similar storage moduli to those of natural rubber/carbon black composites containing 40 parts carbon black (Fig. 9)33.

TOCNs are initially prepared as aqueous dispersions. Therefore, because of their thickening, shear-thinning, and Pickering emulsion-forming properties, they are utilized as additives in aqueous inks, water-based paints, and adhesives35. Furthermore, TOCNs can improve mechanical and thermal properties of composites prepared by mixing TOCN dispersions with water-soluble polyvinyl alochol, cellulose ethers, cellulose acetates with low degrees of substitution, and phenolic resins, followed by drying to remove water36,37. Because TOCNs are crystalline nanofibers with high moduli, their uniform distributions in plastics, resins, and rubber composites theoretically lead to high transparency, and better mechanical and thermal properties. In addition, the formation of large amounts of the TOCN/base polymer interfacial layers as the third component is expected to result in further improvement in properties beyond theoretical values38,39. TOCN dispersions with high aspect ratios are presently available as industrial products from two domestic companies and several overseas companies. Spray-dried TOCNs powders with small aspect ratios (or TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanocrystals, TO-CNCs) are also available as commercial products. TOCNs are expensive at present. However, if the applications of TOCNs are expanded to other fileds and used in various other functional materials, and production quantity is much increased, the price of TOCNs will be expected to decrease. This is because the price of the principal raw material, paper pulp, is ~100 yen/kg. The increases in production quantity and expansion of applications are therefore expected to not only high-performance materials but also commodity products, leading to the creation of a sustainable society based on renewable biomass resources.