Carl Verkoelen

Dr. Carl Verkoelen received a BSc in Analytical Chemistry at the Van't Hoff Institute in Rotterdam and a BSc in Clinical Chemistry at the Polytechnical University in Delft. In 1990 he moved to the Department of Urology of the Erasmus University Rotterdam where he undertook studies on role of renal tubular cells in renal stone disease. Initially, he focused on renal oxalate transport and later his work centered on the retention of crystals in the kidney. In 1998 he obtained the PhD at the Erasmus University Rotterdam. Currently, Dr. Verkoelen is a senior scientist at the Department of Urology, Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam.

Hyaluronan is a large (>106 Da) linear glycosaminoglycan composed of repeating units of glucuronic acid (GlcUA) and N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) dissaccharides. In physiological solutions, hyaluronan behaves like a polyanionic macromolecule due to the negatively charged carboxyl (COO-) group of the GlcUA moieties. The long hyaluronan chains form viscoelastic three dimensional entangled molecular networks that occupy large volumes of water and bind cations1. Hyaluronan has a central role in a number of processes that can ultimately lead to renal stone disease, including urine concentration, crystallization inhibition and crystal retention.

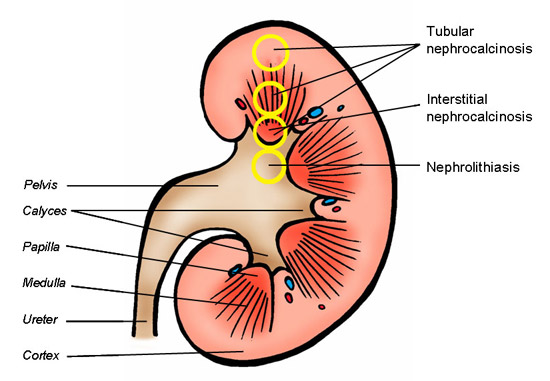

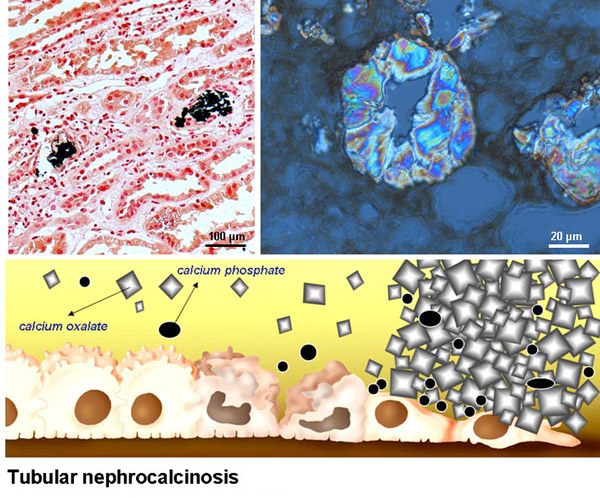

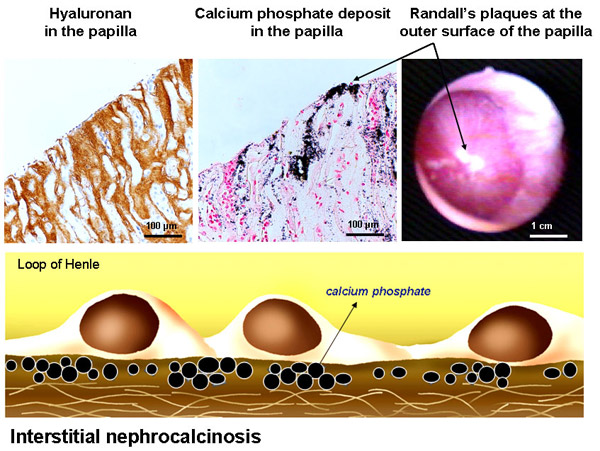

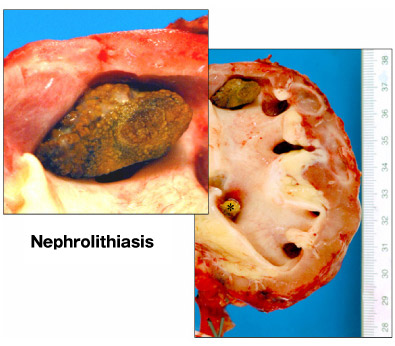

There are three manifestations of renal stone disease; nephrolithiasis (kidney stones), tubular nephrocalcinosis (crystal deposits in the renal tubules) and interstitial nephrocalcinosis (crystal deposits in the medullary interstitium) (Fig.1) 2. Nephrolithiasis is a major health problem in the Western world afflicting 10-15% of the population during their lifetime in the United States with $2.1 billion of medical costs per year3,4. Crystalline material deposited in the medullary interstitium eventually may erode through the wall of the renal papillae to become a nidus for stone growth in the renal calyces. It is not entirely clear if tubular nephrocalcinosis contributes to kidney stone formation, or that this is an entirely independent form of renal stone disease.

Fig. 1

Kidney anatomy and the localization of the different manifestations of renal stone disease. Tubular nephrocalcinosis can take place anywhere in the nephrons, while interstitial nephrocalcinosis exclusively takes place in the inner medulla (papilla) of the kidney.

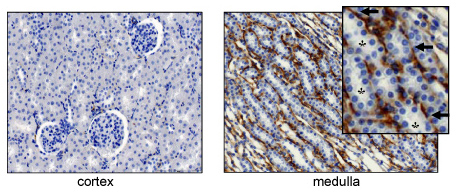

Hyaluronan is abundant in the interstitium of the renal medulla, but nearly entirely absent in the renal cortex (Fig.2). The biosynthesis of hyaluronan is upregulated in developing kidneys and in various renal disease states. Under these conditions, hyaluronan is also expressed in the renal cortex5-7. Hyaluronan is not expressed by renal tubular cells in the healthy kidney. On the other hand, hyaluronan is expressed on the luminal surfaces of developing and regenerating renal tubular cells during respectively, embryogenesis and wound healing8-10.

Fig. 2

Hyaluronan in the healthy kidney. Histological tissue sections made from the renal cortex and medulla and stained with biotinylated hyaluronan binding protein (bHABP). Hyaluronan is abundant in the medulla, but practically absent in the cortex. In the medulla (arrows), hyaluronan is expressed in the interstitium, not in the renal tubules (asteriks).

Metabolic waste products enter the kidney at the glomerulus to be excreted ultimately with urine. Although primary urine becomes supersaturated with calcium salts in the Loop of Henle, tubular actions generate tubular fluid in the early distal tubule that is hypotonic to plasma. From that area to the final urine, calcium; salt supersaturation in the tubular fluid largely depends on the activity of the anti-diuretic hormone arginine vasopressin. Arginine vasopressin increases water permeability of the distal tubule and collecting ducts by membrane insertion of the selective water channel protein, aquaporin 211. The high osmolality in the medullary interstitium subsequently provides the osmotic gradient required for the passive diffusion of water out of the tubules into the interstitium. The expansive domains of the renal medullary interstitial hyaluronan has the ability to occupy large volumes of water and thereby hyaluronan has been proposed to have an important role in renal water handling12,13. The hyaluronan content in the medullary interstitium is high during water diuresis and low during anti-diuresis, indicating that high hyaluronan impedes renal water reabsorption14-16. Water reabsorption is accompanied by increased interstitial hyaluronidase enzyme activity, with subsequent depolymerization of hyaluronan17-19. Increasing evidence suggests that there is also an urodynamic component involved in urine production and water reabsorption. Schmidt-Nielsen proposes that the renal papilla should be considered a pump. The papillary wall is equipped with a pacemaker that produces rhythmic contractions that moves tubular fluid in the direction of the ureter, and in concert with arginine vasopressin/aquaporin 2, the contractions also drive water into the collecting duct cells and from there into the renal interstitium20,21. In the interstitial space, water enters the hyaluronan network that serves as an organic macroporous ion exchange resin. During the next pelvic contraction relatively purified water is squeezed into the ascending vasa recta to return to the blood stream (Fig.3)13. The selective reabsorption of water leads to increased levels of supersaturation of poorly soluble waste salts (calcium salts) in the primary urine. It is not difficult to suggest that the risk for calcium salt precipitation is also increased in the renal interstitium during water reabsorption, since hyaluronan content is low during this anti-diuretic phase.

Fig. 3

Hyaluronan is a large (>106 Da) linear glycosaminoglycan composed of repeating units of glucuronic acid (GlcUA) and N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) dissaccharides. In physiological solutions, hyaluronan behaves like a polyanionic macromolecule due to the negatively charged carboxyl (COO-) group of the GlcUA moieties. The long hyaluronan chains form viscoelastic three dimensional entangled molecular networks that occupy large volumes of water and bind cations. The wall of the papilla is equipped with a pacemaker that produces rhythmic contractions. With respect to the risk for the development of interstitial nephrocalcinosis, the hyaluronan matrix in the renal medulla should be considered an ion exchange resin (A) that binds calcium2+ thereby preventing the formation of poorly soluble calcium phosphate. During rebound the matrix fills with calcium and phosphate (B) and during the next pelvic contraction (C) relatively calcium-free water is squeezed out of the hyaluronan network into the ascending vasa recta to return to the blood circulation (green=carboxyl groups, blue=water molecules, brown=phosphate, purple=oxalate, and orange= calcium .

An animation of the ion exchance function of the hyaluronan matrix.

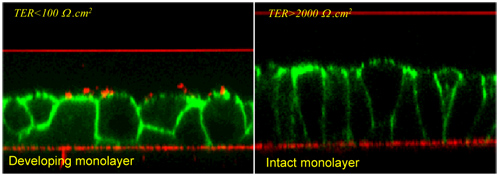

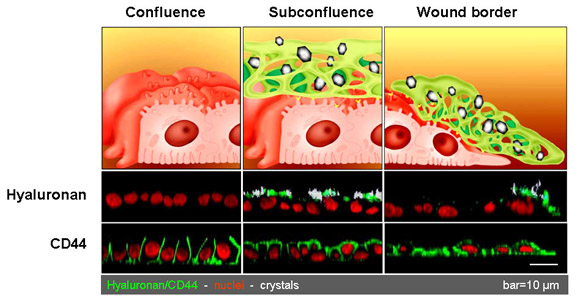

A few decades ago it was proposed that kidney stone formation starts with the retention of crystals in the renal tubules22. Crystal-cell interaction studies performed with renal tubular cells in culture resulted in several candidate cell surface crystal-binding molecules 23-26, including hyaluronan27. Calcium oxalate crystals avidly bind to proliferating and migrating cells in subconfluent cultures or in wounds, but hardly at all to differentiated cells in confluent cultures (Fig. 4) 28. Flattened migrating cells involved in wound healing express hyaluronan at their luminal surface, while differentiated cells in intact monolayers do not (Figs. 5 and 6). Regenerating or proliferating cells also apically express the hyaluronan receptor protein, CD44. During growth to confluence or during wound healing, CD44 is gradually translocated from apical to basolateral domains of the plasma membrane (Fig.7)9. Crystal binding to proliferating and migrating cells is greatly reduced after hyaluronidase treatment 8,27. Wound healing is accompanied by up-regulated hyaluronan synthase 2 (HAS2)-mediated hyaluronan production9. Calcium oxalate crystals appear to have a high affinity for hyaluronan (Fig. 8). The role of hyaluronan in tubular nephrocalcinosis was subsequently studied in rats treated with the nephrotoxic oxalate precursor, ethylene glycol. Calcium oxalate crystals were found in the kidney associated with regenerating tubular cells that expressed hyaluronan and CD44 at their luminal surface (Fig. 9) 10. To determine if these findings are clinically relevant, studies were performed in preterm infants and renal transplant patients, two conditions frequently associated with tubular nephrocalcinosis29,30. In both patient groups, crystals were found together with cell surface hyaluronan and CD44 in the renal tubules (not shown) 31. In preterm neonates renal tubular cells may synthesize and express hyaluronan because these kidneys are still undergoing development. In transplanted kidneys, however, renal tubular cells probably express hyaluronan due to renal tissue damage induced by ischemia and immunosuppressive drugs.

Fig. 4

Images of MDCK- I cells, model for the renal collecting ducts. Confocal laser scanning microscopic (CLSM) scans are made perpendicular to the growth substrate. The cell membrane is visualized with fluorescently (FITC)-labeled phalloidin (green). The developing monolayers in the left image are composed of relatively undifferentiated cells

seeded two days earlier (day=0) at high density on a permeable growth substrate

(Transwells). The transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) across these cultures is still low indicating the absence of functional tight junctions. In time, the cells become higher in

shape, more compact and the tight junctions are assembled as indicated by high TERs. Under these conditions an intact epithelium is formed in 4 to 5 days.

Calcium oxalate crystals are added at the luminal side of the cells and incubated for a certain period of time. After that, all non-adhered crystals are washed away. Crystals are

visualized by light reflection (red dots). The red lines are the growth substrates and cover slips reflecting the laser light. Crystals bind to migrating cells in developing cultures, but

not to cells in intact monolayers, suggesting that a functional healthy epithelium is protected from crystal retention. This may explain why we all form and excrete crystals without

developing renal stone disease.

Fig. 5

Hyaluronan is expressed by cells that are involved in wound healing. Intact monolayers of MDCK-I cells are scrape-damaged with the tip of a pipette. (A) Three cells in an intact monolayer visualized by scanning electron microscopy and (B, t=0 h) five million cells in the same intact monolayer visualized under phase-contrast light microscopy. (B) Shows the entire growth substrate (24 mm in diameter) covered with an intact epithelium (t=0 h left), a scrape damaged epithelium (t=0 h, right), cells infiltrating the wounds one day post injury (t=24 h), and wounds filled again with cells two days post-injury (t=48 h). Five days post-injury the TERs are high again (not shown).

The purple hematoxylin-stained images on top of (C) are higher magnifications of the images shown in (B), at 0, 1, 2 and 4 days post-injury. The dotted squares indicate where the confocal microscopy (CLSM) images shown below are taken. In the CLSM studies cells are stained red with propidium iodide and hyaluronan is stained green with bHABP-FITC. The results show that hyaluronan is not expressed by an intact (day=0) or healed (day=4) epithelium. Hyaluronan is expressed by the flat migrating and proliferating cells that are infiltrating the wound (day=1), and by cells that are pilling up to form a scar at sites where the wounds are closed (day=2).

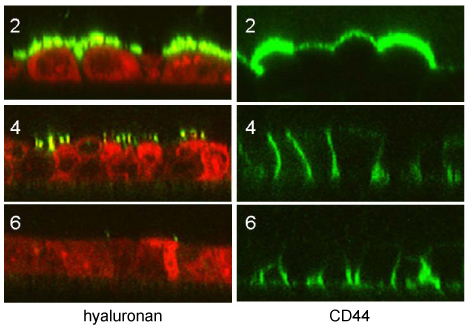

Fig. 6

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) scans made perpendicular to the growth substrate (xz-scans) of MDCK strain I cells in confluent-(left) and subconfluent (middle) cultures, and during repair of scrape injury (right). The cells are incubated for one hour with calcium oxalate monohydrate (COM) crystals and then stained for hyaluronan, and the hyaluronan receptor CD44. All non-adhered crystals are removed by washings, thus all remaining crystals are firmly attached to the cell surface. Confluent monolayers with high TERs ( indicative for functional tight junctions) do not express hyaluronan, express CD44 exclusively at the basolateral plasma membrane and are non-adherent to crystals. Crystals avidly bind to subconfluent cultures expressing luminal hyaluronan and CD44. Crystals also avidly bind to the migrating cells at a wound edge and also these cells express hyaluronan and CD44 at their luminal surface.

Fig. 7

Hyaluronan is expressed by proliferating renal tubular cells in subconfluent cultures (2 days post-seeding). At cell-cell contact (4 days post-seeding) this staining starts to fade away to completely disappear when the tight junctions are assembled (5-6 days post-seeding).

The hyaluronan receptor CD44 is also expressed at the luminal surface in subconfluent cultures (2 days post-seeding), at cell-cell contact CD44 is targeted to lateral spaces, whereas at confluence (6 days post-seeding), CD44 is exclusively expressed at basal domains of the plasma membrane.

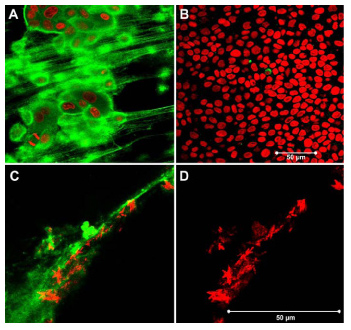

Fig. 8

A) Pericellular matrix rich in hyaluronan associated with the surface of mobile MDCK-I cells visualized by confocal microscopy. B) Confluent monolayers do not express hyaluronan. C) Calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals attached to hyaluronan. D) Light reflection of crystals only. Green in A and C; hyaluronan stained with biotinylated hyaluronan binding protein (bHABP) coupled to avidin-FITC. Red in A and B; nuclei stained with propidium iodide after membrane permeabilization with ethanol. Red in C and D are calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals reflecting in the laser light.

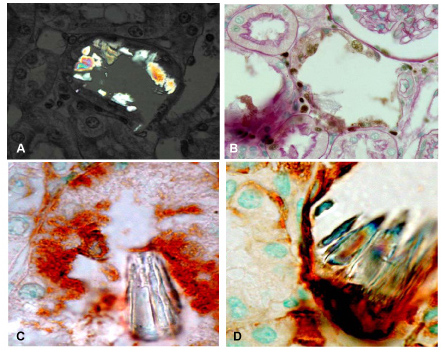

Fig. 9

Renal tissue of rats treated for 8 days with the nephrotoxic oxalate precursor ethylene glycol (0.75% added to the drinking water).

(A) Calcium oxalate crystals visualized by polarized light microscopy and

(B) in PAS and methyl green stained sections associated with the surface of flattened PCNA-positive renal tubular cells.

(C) Crystals are retained by renal tubular cells that express luminal hyaluronan and

(D) CD44.

Calcium salt concentrations in the renal papillary interstitium are far beyond the upper limits of metastability32. Nevertheless, these poorly soluble salts do not easily precipitate because most of the free calcium ions are most likely associated with the carboxyl groups of the GlcUA moieties of hyaluronan. A subset of kidney stones grows on Randall's plaques, these are calcified areas at the surface of the renal papillae33,34. Such plaques are composed of calcium phosphate precipitated in the renal papillary interstitium. This precipitated material becomes a Randall's plaque after its progressive accumulation and ultimately breaking through the wall of the renal pelvis. Stones are more often found in kidneys with Randall痴 plaques and urine of such patients is usually high in calcium and low in volume and pH35,36. In contrast to healthy subjects, the conditions in the renal interstitium must be favorable for calcium phosphate formation in patients with stones. Calcium phosphate formation in the renal papillary interstitium may result from elevated calcium and phosphate concentrations, from shifts in the local pH, or from a larger pool of free calcium ions that result from reduced levels of hyaluronan.

Hyaluronan is not only excellent in retaining water and binding cations1,13, it also avidly binds crystals27. The synthesis and expression at the cell surface of hyaluronan by developing or regenerating distal renal tubular cells inevitably leads to tubular nephrocalcinosis (Fig.10). It is possible that the obstruction caused by this form of renal stone disease results in the loss of total nephron mass. In preterm infants, this may lead to reduced renal function in adulthood, while in renal transplant patients it may have a negative impact on long-term graft survival37. Due to its ability to bind calcium ions, hyaluronan is also an excellent inhibitor of crystallization in the renal papillary interstitium. It is tempting to speculate that interstitial nephrocalcinosis can be prevented by increasing the hyaluronan content. Interstitial nephrocalcinosis ultimately leads to Randall's plaques (Fig.11) and kidney stones (Fig.12). Increasing hyaluronan in the papillae may therefore also have a beneficial effect on kidney stone prevention. The hyaluronan content in the renal papillary interstitium can be increased by increasing daily fluid intake. Remarkably, recurrent calcium oxalate stone formers tend to produce low urine volume38,39. Although it is often assumed that this is caused by environmental factors, lifestyle, or occupation, it is also conceivable that a subset of patients produce low urine volumes due to abnormalities in their renal water handling. This may explain why high fluid intake remains the mainstay of kidney stone prevention40,41. It is often unknown why some individuals continue to form kidney stones (idiopathic recurrent stone formers). This article demonstrates that hyaluronan is likely to be involved in the pathophysiology of all different manifestations of renal stone disease. Better understanding of the factors and mechanisms involved in renal hyaluronan synthesis, deposition and breakdown may lead to more successful treatment strategies.

Fig. 10

Top left: Retention of calcium oxalate crystals in the renal tubules after kidney transplantation. Top right: Close-up image of calcium oxalate crystals plugging the renal tubules of a primary hyperoxaluria patient with end-stage renal failure. Obstruction of the renal tubules leads to tubular necrosis and loss of the total nephron mass. In preterm infants, tubular nephrocalcinosis may lead to reduced renal function in adulthood, while in renal transplant patients it may have a negative impact on long-term graft survival.

Fig. 11

Top left: Hyaluronan stained with hyaluronan binding protein (HABP) is found in interstitial spaces of the renal papilla, but not in the renal tubules. Top middle: crystal deposits stained with the Yasue calcium staining method is found at the same locations as hyaluronan. The arrow shows calcium deposits eroded through the papillary wall forming Randall's plaques at the outer surface. Top right: Randall's plaques as urologists encounter them with scopes during percutaneous nephrolithotomy (see film). These plaques form a nidus for kidney stones to grow on.

Fig. 12

The right image shows calcium oxalate stones in a kidney removed due to chronic pyelonephritis. One large stone is located in the renal calyx (see also inset) and a smaller one is obstructing the ureter (asterisk).

Acknowledgements. These studies were supported by the Dutch Kidney Foundation (www.nierstichting.nl), the Oxalosis and Hyperoxaluria Foundation (www.ohf.org), the Foundation Scientific Urological Research (www.suwo.org). I thank Robert Stern (Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, University of California, USA) and Dirk-Jan Kok (Department of Urology, Erasmus MC Rotterdam, The Netherlands) for carefully reading the manuscript and valuable discussions, Nihal Yildirim for all the beautiful illustrations and animations and Paul Verhagen (Department of Urology, Erasmus MC Rotterdam, The Netherlands) for his film on Randall痴 plaques. Furthermore, I would like to thank my collaborators Marc de Broe, Anja Verhulst, Benjamin Vervaet and Patrick D辿ease from the laboratory of pathophysiology of the University of Antwerp, Belgium and Hans Romijn, Marino Asselman, Marieke Schepers, Burt van der Boom, Eddy van Ballegooijen, Charlie Laffeber, Fritz Schröder and Chris Bangma.