Yu Nakagawa

Associate Professor, iGCORE, Nagoya University

He graduated Kyoto University in 1997 and obtained his Ph.D. degree in Agriculture from the same university in 2002. After training as a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) research fellow (DC1, PD) at Kyoto University (Kazuhiro Irie Lab) and a postdoc at Stanford University (Paul A. Wender Lab), he joined RIKEN (Yukishige Ito Lab) as a research scientist and was promoted to a senior research scientist. In 2014, he became an associate professor at Nagoya University (Makoto Ojika Lab) and then joined iGCORE. He received a Young Scientist’s Research Award in Natural Product Chemistry (2009), Japan Society of Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Agrotechnology (JSBBA) Award for Young Scientists (2011), and JSBBA Innovative Research Program Award (2024).

Pradimicin A (PRM-A) is a natural product derived from actinomycetes. Since its discovery as a unique compound with an ability to bind mannose (Man) in the 1990s, much attention has been paid to the molecular basis of Man recognition by PRM-A. However, aggregation of PRM-A in solution has severely limited our understanding of how PRM-A recognizes Man. Over the past decade, our work addressed this issue by using solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) methods and finally resulted in a reliable molecular model of Man binding to PRM-A. We have also demonstrated that PRM-A could be applicable to detection of Man-containing glycans and suppression of pathogen infections. This article outlines our studies related to the molecular basis of Man recognition by PRM-A and discusses its possible applications to glycobiological research and drug development.

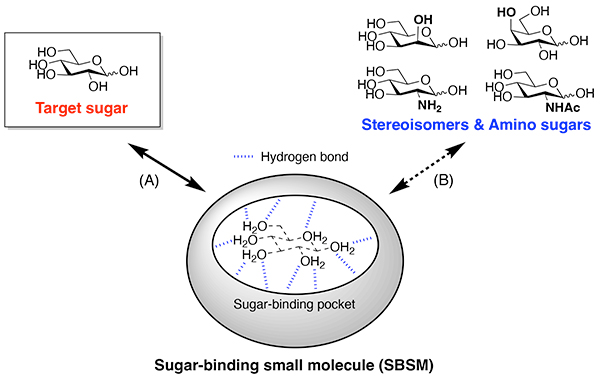

There is growing evidence that glycans displayed on proteins and lipids are involved in a variety of biological and pathological processes1-4. The emerging significance of glycans has progressively increased the demand for sugar-binding small molecules (SBSMs) that can be employed as tools to analyze glycan functions and as drug leads for glycan-related diseases. Nevertheless, it is quite challenging to develop SBSMs that remain active in water (Figure 1)5. The predominant issue is the competition between sugars and water molecules. The polyol structure of sugars is seemingly similar to the structure of water molecule clusters, making it difficult for SBSMs to replace water molecules in their sugar-binding pockets with sugar molecules. Structural similarity among sugar molecules causes another issue of binding selectivity. For example, glucose differs from Man and galactose (Gal) only in configuration at one or two stereocenters, and also structurally resembles amino sugars such as glucosamine and N-acetyl-glucosamine (GlcNAc). Thus, developing SBSMs that discriminate the target carbohydrate from its stereoisomers and amino derivatives is a difficult task even for experts in the field of supramolecular chemistry. Man, especially, is one of the monosaccharides that is quite hard to capture in water, and there remains a general lack of synthetic small molecules that specifically bind Man in water.

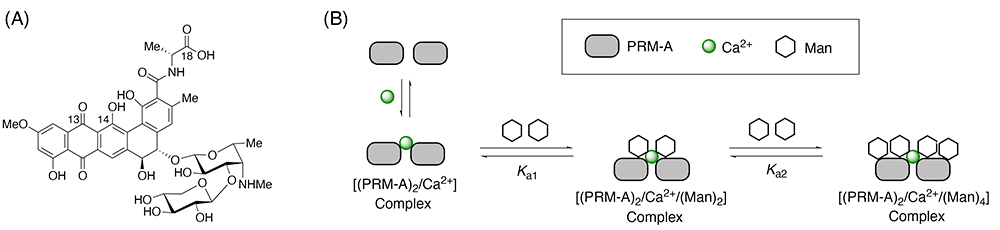

On the other hand, nature produces a unique SBSM with Man-binding ability. Pradimicin A (PRM-A, Figure 2A) was isolated from Actinomadura hibisca in 1988 as an antifungal compound that binds Man in the presence of Ca2+ ion6,7. Since the discovery that PRM-A behaves like C-type lectins, much attention has been directed toward its Man-binding mechanism. Intensive studies in the 1990s found that two molecules of PRM-A are bridged by Ca2+ ion to form the dimeric [(PRM-A)2/Ca2+] complex, which binds four molecules of Man in two steps (Figure 2B)8,9. However, structural analysis of the [(PRM-A)2/Ca2+/(Man)2] and [(PRM-A)2/Ca2+/(Man)4] complexes by X-ray crystallographic and solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) approaches has been severely limited by their high propensity to aggregate. As a result, the Man-binding mechanism was not elucidated for more than 30 years after the discovery of PRM-A.

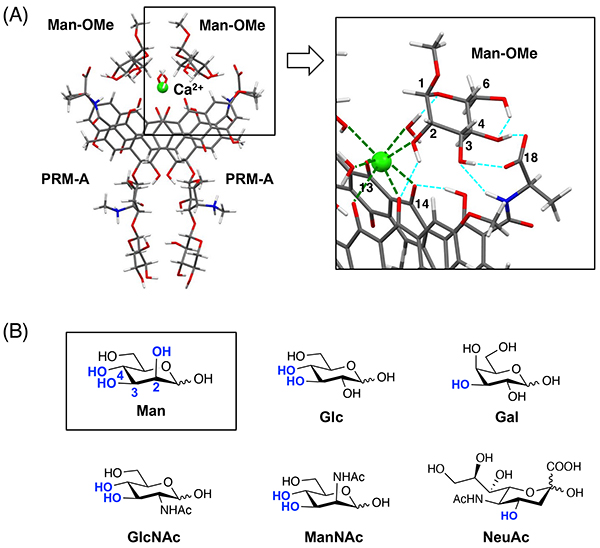

To address the issue related to aggregation of PRM-A, we developed a unique analytical approach based on solid-state NMR spectroscopy10-12. Our approach involves the preparation of solid aggregates, mainly of the [(PRM-A)2/Ca2+/(Man)2] complex, by using 13C-labeled PRM-A and methyl α-D-mannopyranoside (Man-OMe) and the evaluation of intermolecular 13C—13C distances in the complex by using a two-dimensional solid-state NMR technique, DARR (dipolar assisted rotational resonance)13,14. Based on the obtained interatomic distances in the complex and the crystal structure of the dimeric Ca2+ complex of PRM-A derivative, we finally disclosed a reliable structure of the [(PRM-A)2/Ca2+/(Man-OMe)2] complex through DFT (density functional theory) calculations15. As shown in Figure 3A, two molecules of PRM-A stack with each other through Ca2+ coordination at the C13 carbonyl and C14 phenolic hydroxy groups. Two molecules of Man-OMe bind to the [(PRM-A)2/Ca2+] complex in a symmetrical fashion. The 2-, 3-, and 4-hydroxy groups of Man-OMe interact with PRM-A through Ca2+ coordination and/or hydrogen bonding, whereas the 1-methoxy and 6-hydroxy groups hardly contribute to the complex formation. This binding mode suggests that the spatial array of the 2-, 3-, and 4-hydroxy groups of Man is pivotal for Man recognition by PRM-A, which clearly explains the fact that PRM-A is insensitive to common monosaccharides other than Man, such as Glc, Gal, GlcNAc, N-acetyl-mannosamine (ManNAc), and N-acetyl-neuraminic acid (NeuAc) (Figure 3B)15,16.

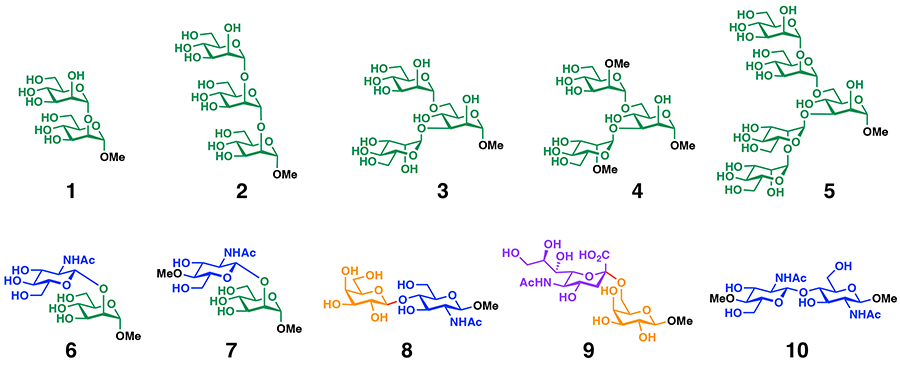

Man recognition by PRM-A can be used as the molecular basis for oligosaccharide binding to PRM-A. For example, binding experiments using synthetic oligosaccharide motifs from N-glycans (Figure 4) demonstrate that PRM-A binds to oligomannose motifs (1–3,5) having Man residues at the non-reducing ends but not to the 2-O-methylated trimannose motif (4), disaccharide motifs (6,7) having Man residues at the reducing ends, and disaccharide motifs (8–10) without Man residues17,18.

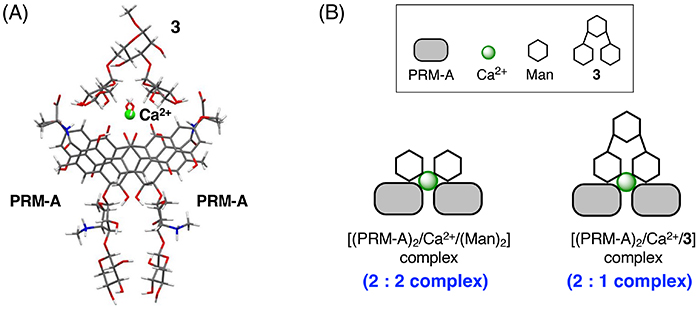

Interestingly, PRM-A exhibits about 16-fold higher affinity for branched oligomannoses (3,4) compared with linear oligomannoses (1,2) and Man. Detailed binding analysis of PRM-A and 3 suggests the formation of the [(PRM-A)2/Ca2+/3] complex (Figure 5A), in which two Man residues at the non-reducing ends of 3 simultaneously bind to the Man-binding sites of the [(PRM-A)2/Ca2+] complex. This binding mode minimizes the entropic loss associated with the complex formation, which could be a major reason why PRM-A prefers to bind to branched oligomannoses (Figure 5B).

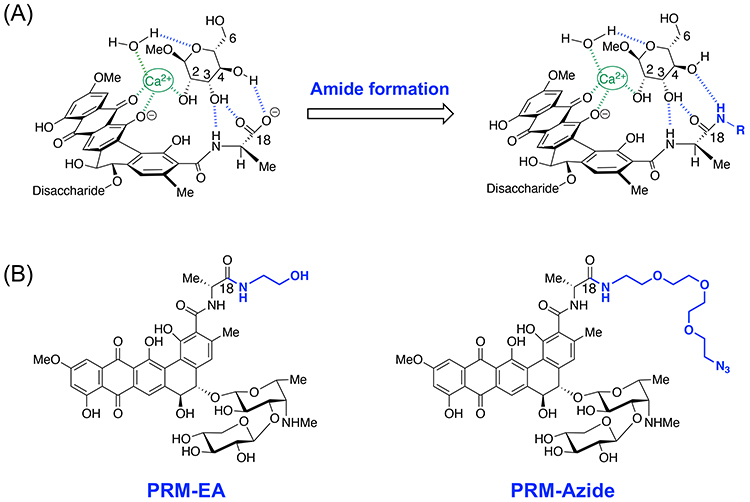

Having demonstrated that PRM-A can bind Man-containing glycans, we decided to develop PRM-A derivatives that can be used for glycobiological studies. The molecular modeling based on the [(PRM-A)2/Ca2+/(Man-OMe)2] complex suggests that the C18-amide derivatives of PRM-A could bind Man through the interaction with the 2-, 3-, and 4-hydroxy groups of Man (Figure 6A). According to this design concept, we developed two amide derivatives of PRM-A (PRM-EA, PRM-Azide)15,19 (Figure 6B). Binding experiments confirmed that although Man binding affinities of these amide derivatives are about five times lower than that of PRM-A, they can definitely recognize Man.

Surprisingly, these amide derivatives show little aggregation when binding to Man. By taking advantage of this favorable property along with their inherent red color, PRM-EA was employed to stain glycoproteins in dot blot assays19. As shown in Figure 7, PRM-EA stained ovalbumin (OVA) and thyroglobulin (Tg) carrying high-mannose-type and hybrid-type N-linked glycans with Man residues at the non-reducing ends. No staining was observed for transferrin (Tf) and immunoglobulin G (IgG), both of which possess only complex-type N-linked glycans with no Man residues at the non-reducing ends, and no staining was observed for bovine serum albumin (BSA) without N-glycans. Such staining selectivity is not observed in the pre-existing dyes, highlighting the potential of PRM-EA as a new research tool for selective detection of glycoproteins with terminal Man residues.

On the other hand, PRM-Azide was used for fluorescent detection of fungal glycans15. After attachment to cell-wall mannans (polymannose glycans) of living fungal cells (Candida rugosa), PRM-Azide was conjugated to an alkyne-containing fluorescent tetramethyl rhodamine (TAMRA) tag via its azide group by means of Click chemistry. As shown in Figure 8, clear fluorescence was observed on the surface of the fungal cells by this two-step protocol. The absence of either PRM-Azide or TAMRA tag resulted in almost disappearance of fluorescence, suggesting that the observed fluorescence is derived from the PRM-Azide-TAMRA conjugate. These observations suggest that PRM-Azide may be suitable for the fluorescence staining of Man-containing glycans.

PRM-A shows a broad spectrum of in vitro and in vivo antimicrobial activities against pathogenic fungi, such as Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Aspergillus fumigatus, without significant cytotoxicity against mammalian cells and acute toxicity against mice7. Importantly, PRM-A has no cross-resistance to major classes of antifungal agents, such as amphotericin B, 5-fluorocytosine, and ketoconazole, suggesting that PRM-A could be a promising lead compound for unique antifungal drugs. However, PRM-A-based drug development has been hampered by extensive PRM-A aggregation in the presence of serum ionized Ca2+ at concentrations of 1.1–1.2 mM.

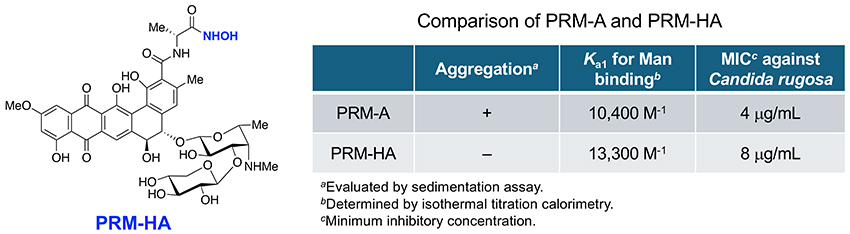

Encouraged by the finding that PRM-EA and PRM-Azide hardly showed any aggregation in Ca2+-containing aqueous solutions, we synthesized a series of amide derivatives of PRM-A to explore alternative drug leads. Among them, PRM-HA with a hydroxyamide functionality was comparable to PRM-A at binding Man and preventing fungal growth without showing significant aggregation (Figure 9)20. Structural optimization of PRM-HA is currently underway to further the development of PRM-A-based antifungal drugs.

Very recently, we found that PRM-A can inhibit in vitro infection of SARS-CoV-2 (IC50 = 1.2 µM)18. The anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of PRM-A was significantly attenuated in the presence of branched oligomannose (3), suggesting that the molecular targets of PRM-A might be high-mannose-type and/or hybrid-type N-glycans on the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Notably, PRM-A hardly shows cytotoxicity against human lung epithelium-derived Calu-3 cells used for the SARS-CoV-2 infection assay (CC50 >100 µM). These results collectively indicate that PRM-A could also be a promising drug lead for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

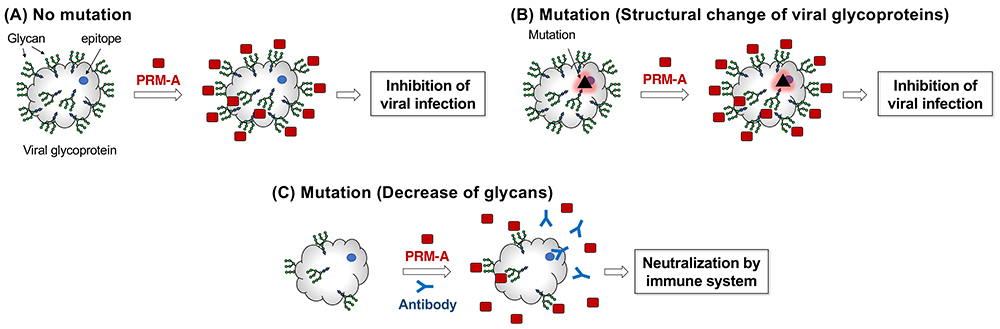

Accumulated evidence suggests that N-glycans on viral envelopes act as a shield to hide and protect epitopes from the host immune system21,22. When considering this role of viral glycans, it is expected that PRM-A could be effective against various viral variants23. Since the molecular targets of PRM-A are not proteins but glycans (Figure 10A), PRM-A would be insensitive to structural change of viral proteins induced by mutations (Figure 10B). If viruses escape from PRM-A by mutation to decrease N-glycans on the envelope glycoproteins, the epitopes become exposed to the host immune system, leading to neutralization and elimination of the virus (Figure 10C). Thus, treatment with PRM-A presents the virus with a dilemma: either it is removed from the host by being kept suppressed by PRM-A binding or it escapes the effect of PRM-A binding by decreasing the level of N-glycans, which leaves the virus vulnerable to neutralization by the immune system. Although this antiviral concept is still in the early phase of “proof-of-concept,” PRM-A may become a universal antiviral drug that can suppress infection by all virus variants.

Although PRM-A received attention as a unique natural product with Man-binding ability, its scientific significance has not been well recognized in the three decades following its isolation in 1988. However, the biological potential of PRM-A and other SBSMs has been recently implicated in association with the emerging biological roles of the glycans highlighted above. In addition to PRM-A, a plant-derived poacic acid is reported to exhibit antifungal activity by binding to β-1,3-glycans in the fungal cell wall, and thereby has a great potential to become glycan-targeted pesticides24,25. Supramolecular chemistry has been used to develop artificial SBSMs with medicinal potential in recent years26-29. With further advancement of this field, SBSMs are likely to make a significant contribution to the future carbohydrate research and drug development.