|

If we accept the scenario on the origin of glycans and their

diversification by bricolage, as mentioned at the beginning of this chapter

(ES-00),

lectins for recognizing glycans may represent part of the scenario and

possibly have some “deviation” in their distribution and function

(specificity) in organisms. For example, lectins that recognize glucose

and mannose (aldohexoses which constitute the first triplet in the above

scenario) are assumed to function for fundamental biological activities

because these saccharides are believed to be older than the other saccharides.

In contrast, lectins that recognize late-comer saccharides, such as galactose,

sialic acid, etc. (explainable as bricolage products derived from glucose

and mannose), function for relatively limited activities in higher and

more complicated life forms. This scheme, however, may not be applied

to every lectin, and is limited to proving the link between the evolution

of glycans and the evolution of life.

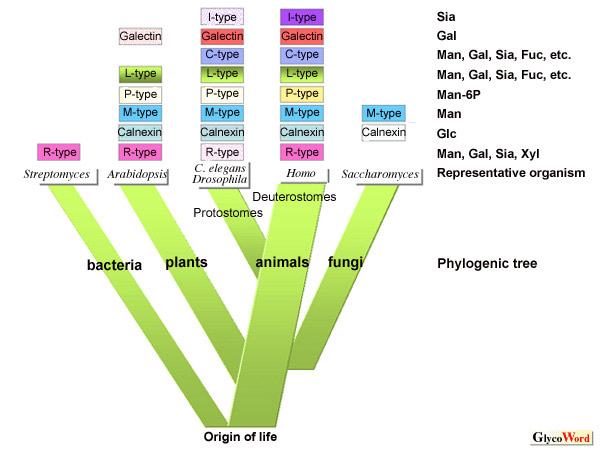

Lectins number approximately twenty families including carbohydrate recognition

domains in enzymes (the domains in enzymes of carbohydrate recognition

that mediate binding to target molecules, CRD), whereas lectin proteins

are known to have a variety of structures. About ten families of lectins

in animals have been well studied, as shown in Figure

1. With progress in genome analysis, homologous genes have been

revealed to exist in model organisms other than humans, renewing attention

from the viewpoint of relationship between structure and function. For

example, Prof. Drickamer et al. (http://www.imperial.ac.uk/research/animallectins/)

claim that more than 120 C-type lectin genes (LE-A04)

exist in the nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans), which is a model

organism representing multicellular animals and has been analyzed earlier

than others. More than 10 galectins (LE-A01),

which are lectins that recognize  -galactoside,

are known to exist in the worm, and have been analyzed for their functionality

to some extent. Since glycoconjugates are not well understood, we do not

know to what extent the processing capability of complex type N-linked

oligosaccharides is preserved in these invertebrates and vertebrates including

humans. They are, however, presumably galectins that function as receptors,

represented by galactose recognition, specifically existing in multicellular

organisms due to the fact that no homologue genes have been found yet

in yeast. Further, siglecs are pointed out as typical lectins specific

to higher animals. This lectin family belongs to the immunoglobulin superfamily

of proteins (classified into an I-type lectin family) and has functions

specific to vertebrates (LE-B04),

such as a variety of cell-signal controls, specific recognition of sialylated

oligosaccharides, etc. The siglecs are understood to have proliferated

rapidly at a latter stage of evolution, due to the fact that the siglecs

are poorly homologous among species and almost all siglecs cluster themselves

at a same place on chromosomes. In contrast, R-type lectins (LE-A08)

are pointed out as common lectins (CRD) among microorganisms. The lectins,

named after a ricin B-chain, often function as an AB-type toxin and a

subdomain in enzymes. Ricin, which is a plant toxin, is specific to galactose

and is obviously targeted in animal cells, whereas the lectin CRD, distributed

in a vast range of organisms, shows a variety of specificity to sialic

acid, mannose, xylose, etc., together with galactose. An R-type lectin

domain exists, almost without exception, at the C-terminal of peptide-N-acetyl-galactosaminyltransferases

(ppGalNAcT) that catalyze the first step of muchin-type oligosaccharides

synthesis (transfer N-acetyl-galactosamin (GalNAc) to a polypeptide

chain), and contributes to form a muchin cluster. Sambucus sieboldiana

lectin (SSA) and Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA) that are known as

representative lectins specific for sialic acid, belong to the R-type

lectin family. It can not be denied, as of now, that the genes of these

lectins spread by the horizontal gene transfer from prokaryotes to eukaryotes,

or vice versa, though the R-type lectins, which show specificity to a

variety of glycans and are abundant in organisms, seem to have nothing

to do with the relationship between the origin of glycans and evolution

which is proposed here. -galactoside,

are known to exist in the worm, and have been analyzed for their functionality

to some extent. Since glycoconjugates are not well understood, we do not

know to what extent the processing capability of complex type N-linked

oligosaccharides is preserved in these invertebrates and vertebrates including

humans. They are, however, presumably galectins that function as receptors,

represented by galactose recognition, specifically existing in multicellular

organisms due to the fact that no homologue genes have been found yet

in yeast. Further, siglecs are pointed out as typical lectins specific

to higher animals. This lectin family belongs to the immunoglobulin superfamily

of proteins (classified into an I-type lectin family) and has functions

specific to vertebrates (LE-B04),

such as a variety of cell-signal controls, specific recognition of sialylated

oligosaccharides, etc. The siglecs are understood to have proliferated

rapidly at a latter stage of evolution, due to the fact that the siglecs

are poorly homologous among species and almost all siglecs cluster themselves

at a same place on chromosomes. In contrast, R-type lectins (LE-A08)

are pointed out as common lectins (CRD) among microorganisms. The lectins,

named after a ricin B-chain, often function as an AB-type toxin and a

subdomain in enzymes. Ricin, which is a plant toxin, is specific to galactose

and is obviously targeted in animal cells, whereas the lectin CRD, distributed

in a vast range of organisms, shows a variety of specificity to sialic

acid, mannose, xylose, etc., together with galactose. An R-type lectin

domain exists, almost without exception, at the C-terminal of peptide-N-acetyl-galactosaminyltransferases

(ppGalNAcT) that catalyze the first step of muchin-type oligosaccharides

synthesis (transfer N-acetyl-galactosamin (GalNAc) to a polypeptide

chain), and contributes to form a muchin cluster. Sambucus sieboldiana

lectin (SSA) and Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA) that are known as

representative lectins specific for sialic acid, belong to the R-type

lectin family. It can not be denied, as of now, that the genes of these

lectins spread by the horizontal gene transfer from prokaryotes to eukaryotes,

or vice versa, though the R-type lectins, which show specificity to a

variety of glycans and are abundant in organisms, seem to have nothing

to do with the relationship between the origin of glycans and evolution

which is proposed here. |

|

|

On the other hand, calnexin and calreticulin ( ES-B01),

which are related to the folding of glycoproteins, are lectins that

recognize a non-reducing-end glucose residue in an N-linked oligosaccharide

precursor, and are likely to possess same specificity and functionality

among all eukaryotes that are understood based on the universality of

the biosynthesis mechanism on N-linked oligosaccharides, whereas

a calnexin gene in yeast has not been proved to function for this purpose.

In the same way, there are a variety of lectins that exist in cells

and are abundant in multicellular organisms: VIP36 and ERGIC53 (ES-C04)

that are mannose-specific lectins as cargo receptors, EDEM-relating

M-type lectins that are homologues to  -mannosidase

but have no catalytic activity, and two homologous lectins (cation-dependent

or -independent mannose-6-phosphate-binding lectins) that recognize

mannose-6-phosphate, a well-studied target tag for lysosomal enzymes.

These lectins in cells have specificity to either glucose or mannose

and are supposed to have arisen at the earliest stage of evolution.

This observation implies that the origin of carbohydrates is certainly

related to evolution.

The above suggests, though not strongly,

that some relationship exists between distribution of lectins in organisms

and common functionality, and between specificity and locality inside

or outside cells. Comparative glycomics tries to understand glycans

in their basic structure and mechanism from the viewpoint of biological

evolution. Such studies may not lead to function analyses of glycans

or to industrial applications. Nevertheless, we cannot escape the issue

of evolution in science, because we all seek the answer to the question,

“How did we get here?” Glycans, even though they are not directly governed

by genes, should not be ignored. |

|

|

| References |

(1) |

Taylor ME, Drickamer K: “Introduction to Glycobiology”, Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2003 |

|

(2) |

Drickamer K, Dodd RB: C-Type lectin-like domains in Caenorhabditis

elegans: predictions from the complete genome sequence. Glycobiology,

9, 1357-1369, 1999 |

|

(3) |

Cooper DN, Barondes SH: God must love galections; he made so many

of them. Glycobiology, 9, 979-984, 1999 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|